A Push for Investment in the South

The Government's National Land Transport Program was released on Tuesday, and its pretty lackluster for anyone south of the Cook Strait. What kind of impact will this (not) have?

For a quick bite on the NLTP as a whole, and some of its drawbacks, I recommend Greater Auckland’s article here. For an opinion on why this NLTP is sending our country hurtling back into car dependency for no good reason, see Timothy Welch’s piece in The Post here.

September 2 saw the release of the Government’s long-awaited National Land Transport Program (NLTP). This document defines the priority for investment in transport projects from the public purse over the next three years. It forms one of the core documents in any Government’s transport portfolio and should be representative of the needs of all citizens in this country.

But if you live south of the Cook Strait, it’s a dud. One might go as far as to say insulting even.

But that’s not surprising to those in the know. Successive governments have failed to invest in the South Island’s transport sector for decades. The only exemptions have been for costly and controversial major roading projects, which have run over time and budget and only created more headaches. Why do we keep getting the short end of the deal?

Roads of National Insignificance

The biggest ticket item on the NLTP’s docket is the revived Roads of National Significance; a Key era program designed to identify and build more roads to improve productivity. Did it work?

If the goal had been to drive up car usage emissions, and traffic, then it worked. The Christchurch Northern Corridor (CNC) and Christchurch Southern Motorway (CSM) have contributed to increased traffic at their ends, clogging neighbourhoods and wreaking havoc on social fabric and safety.

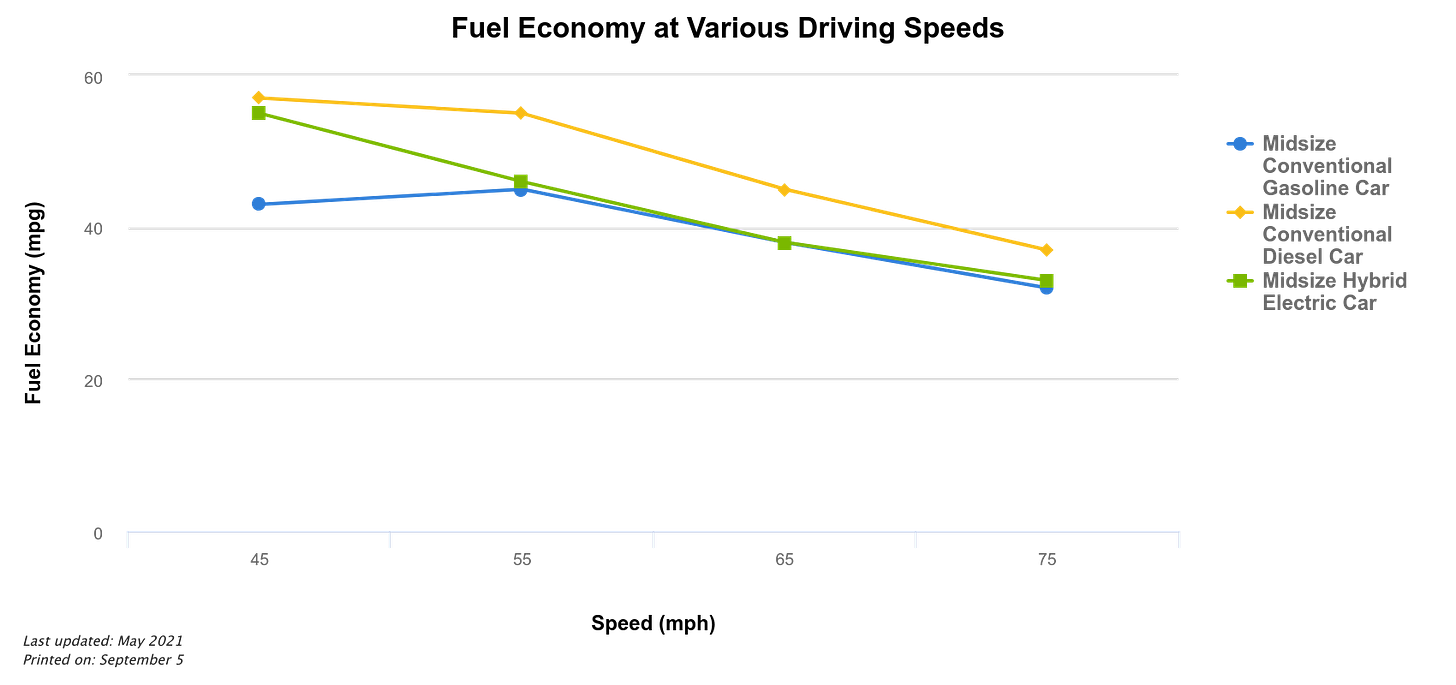

There’s ample evidence to suggest that building new motorways won’t change that equation. Evidence also shows that while increased vehicle speeds do in theory save time, they cost the driver more in fuel consumption than any financial compensation a time reduction could provide. Combining that with an effective one-to-one ratio of road capacity improvement to increased usage and building new motorways makes no sense.

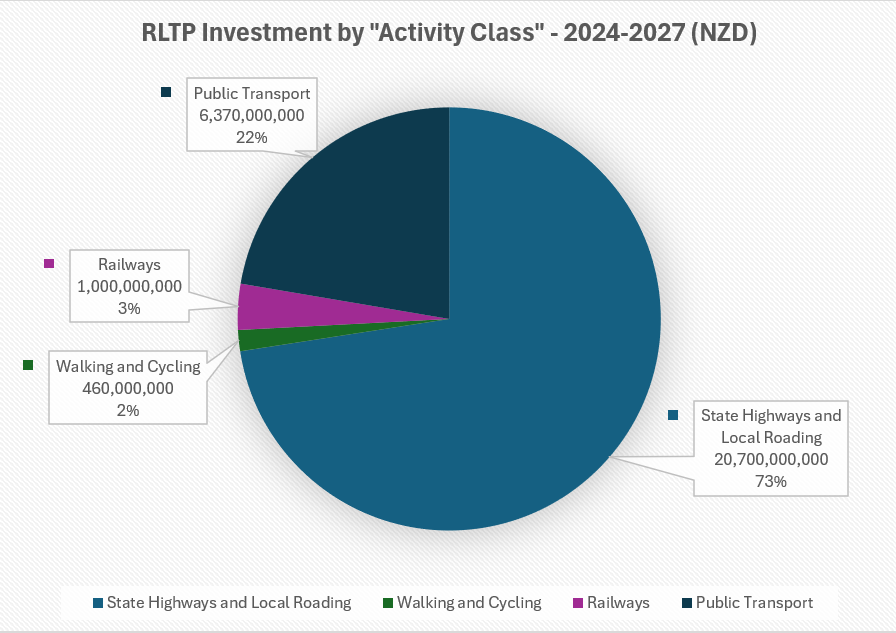

Contrasting this feast for roads, Public Transport funding takes a sharp cut and Active mode funding is effectively obliterated. Good luck finding money for schemes that improve road safety by slowing drivers down, there won’t be any. Say goodbye to speedbumps as, according to Minister Brown, they cost half a million each (they don’t, he knows it, he doesn't care). As before, baseless claims of economic value (without evidence) overrule the need for safer roads.

The truth of this government is that with transport, there is a clear preference for ideology and rhetoric rather than for evidence and reason. Simeon Brown has a long history of framing investments in Public and Active transport as a “War on Cars”. The truth is that a diversified investment portfolio encourages more diverse usage, and less traffic in a single mode. NZTA stated in 2013 that Pubic Transport investment increased productivity between 3% and 23% over other modes such as the private car.

So with all this focus on roads, surely the region with the largest road network (Canterbury) would benefit, right?

Investment? Bah, Humbug!

More than anywhere, this trend of poor investment is manifesting itself in Canterbury. The reality for many years has been that we have always gotten the short end of the stick regarding investment. But, for transport specifically, it has been a chronic issue. The only named investments listed in Canterbury in the NLTP are:

Belfast to Pegasus Motorway and Woodend Bypass

Canterbury Package - Rural Intersections

Canterbury Package - Rolleston Upgrade

Canterbury Package - Halswell

Second Ashburton Bridge

Of the $32.9 billion allocated in the NLTP, Canterbury will receive $1.8 billion in transport funding. Auckland by comparison will receive $3.7 billion for Public Transport alone.

A whopping $8.3 billion alone is allocated to procuring and designing the new RONS (some money is available in Canterbury). However, it should be noted that none of the construction costs for these roads are included in this spending. 8.3 billion to plan, design, and protect corridors for these roads. Not to build anything.

If only Robert Moses were alive to see such a thing. He would probably invite Simeon Brown for dinner and pat him on the back.

For anyone in the South, this should be taken as a clear kick in the teeth. Christchurch is Australasia’s biggest city without a metro or regional rail system. Any investment in Active transport infrastructure designed to turn our city away from its >80% car usage statistic is now gone. Previously cut funding for PT Futures and MRT plans seem entirely off the table, and even measures designed to make our streets safer in the face of bigger and heavier cars driving even more dangerously seem to be off the table.

Canterbury is not on the priority list for this Government.

Per Capita? Cur Tempto.

One of the most damning pieces of evidence that this NLTP will set Canterbury back is the per capita spending. Canterbury, with its strong growing GDP, and most of the fastest growing regions in the country, will receive the lowest per capita spend of any region identified in the program. $2764 per capita to be precise.

Let’s compare that with Wellington, which we have overtaken in both GDP and Population categories. They receive $6334 per capita. Auckland is $5070. For the more nitty gritty, see Charlie Mitchell’s article in The Press about “Canterbury’s missing transport billions” to learn how bad this funding model is.

In short, we pay more into the scheme (~14%) than we receive out by a large measure per capita (~8% 2024-27 RLTP), and have for quite a while now. Our large road network puts significant revenue into the Regional Land Transport Fund (RLTF) which subsequently pays for investment elsewhere, where the political capital is higher. Why is that?

Greater Christchurch surpassed Greater Wellington in population and GDP growth in the late 2010s-early 2020s. Despite our ladder climbing the money doesn’t flow like it should. Brendon Harre has written multiple times about this, but I still find this the best way to describe our city relative to the rest of the country.

Christchurch fills the ‘Chicago second city role’ in New Zealand’s hierarchy of towns and cities, yet this function is poorly recognised…

…Chicago is currently the third largest city in the US; for much of its history, it was the second. It is not the largest commercial city — New York takes that role — or the political capital — Washington DC has that position. Unlike Silicon Valley, LA and California, it is not the centre for the motion picture industry, broadcasting, social media or a particular type of technological expertise and innovation. Still, Chicago is a significant city for the US. For people and firms who want all the amenities of a big city but who have no need to be in the political capital, Chicago is an attractive proposition.

There are other parallels between Chicago and Christchurch; both are hubs for nationally significant rural hinterlands and have city histories of meatpacking and processing agricultural products.

Christchurch suffers from “second city syndrome”. As our nation’s “second city” we are not the political or social capital that Wellington is, nor the economic and population capital that Auckland is. But, we are enticing to visitors, investors, and employers; with some of the cheapest housing and rents of a major city in this country.

We focus on developing upcoming industries and promoting entrepreneurship. This city should be buzzing with capital from the government to support this growth. Yet it seems to be the case every time funding is dished out, we miss out because “we don’t need” the funding, and yet the very trend of constant underfunding makes that so.

No rail? No need for rail funding. Poor public transport? Let’s throw a handful of dollars at it. Different local priorities to our ideology? Looks like you won’t see much money from us. It is a vicious cycle of underinvestment driving underinvestment, and one this government has no qualms of continuing.

What to do about it?

The reality is that the NLTP is now set through to 2027. What that means is projects not covered (read Public Transport, Active transport, traffic calming measures), will now need to be fully covered by local authorities. This one will ping Christchurch particularly hard.

On top of this, the intended result of this NLTP will be to have shovels in the ground on a dozen new car generators (motorways) by the turn of the 2030s with little consideration as to how that money could be better spent or the impact that will have.

We are still being shafted. And that will need a lot of noise to change. Inertia is one of the most problematic parts of government trends, and few governments have tried to reverse the trend of underinvestment in the South. So, what can we do about it at a community level if government policy has already been set and we’ve been left behind?

Join your local Urbanist Group or Residents’ Association and begin to advocate for better things. Most cities have these, and in some instances, they may be required to be consulted on certain items. Having your voice at the table increases the visibility of your cause. Auckland, Wellington, and Christchurch all have well-developed networks of local urbanists with whom you can engage.

Talk to your local representatives. Making yourself heard doesn't just begin and end at the Council table or in the Select Committee process. Your Elected Representatives are there to listen and consider your position, at all levels of government. So book a coffee and have a chat, they’re usually very approachable.

Collect data on, identify, and stay on top of local issues. Something for the more involved is to begin to identify trends and collect basic data at a localised level, perhaps even for a singular problem. You might be the person who sees the issue the most, and no amount of backroom analytics can deny that. Knowing your community and its needs is one of the biggest tools in any advocate’s arsenal.

Push to have projects completed locally. This one draws the ire of fiscally conservative representatives, but not all projects need central government funding. So long as your local representatives believe nothing can be done without that funding, nothing will be done. Let them know that issues shouldn’t be put on hold because central government has a momentary lapse of reason.

But, the biggest thing you need to do is engage with these issues and make yourself heard. Being heard is the first step to change.