Beware the Invisible Hand

We keep being told that "the private market" will fix the inefficiencies of transport and infrastructure in New Zealand. History here and around the world dictates otherwise.

Suppose you want an in-depth history of the impacts of privatisation and government policy on New Zealand’s Railways. In that case, I recommend “Can’t Get There from Here: New Zealand’s Shrinking Passenger Rail Network, 1920–2020” by André Brett (text) and Sam van der Weerden (maps) (also available through Christchurch City Libraries).

Many would argue that dire conditions have existed in New Zealand’s rail network since the 1980s. Deferred maintenance by private companies and chronic underfunding by central governments have often left our network on the brink of failure. Some currently argue that even KiwiRail follows the same path.

The potential cost of a network failure could be travel disruption, economic slowdowns, or, in some cases, even job losses. Almost all in power have failed to properly bring the potential of rail to bear in our economy and society, causing disruption and consequences. Now we stand on the precipice of another round of asset sales and privatisation despite the clear failures of previous attempts.

Why have successive network operators in New Zealand failed to learn from this prophecy?

The Privatisation Era of New Zealand’s Railways

Historically, New Zealand’s railways have almost always been publicly owned and operated. New Zealand Railways (later New Zealand Railways Corporation (NZRC) quickly overtook the early colonial and provincial companies. Corporatisation in 1982 pushed the first domino, and in 1986 NZRC was made an SOE (State-Owned Enterprise) before being sold in 1993.

In a somewhat ironic state of affairs, it was sold to a consortium led by Wisconsin Central; a company formed by Soo Line from the failed Milwaukee Road’s assets. (The Milwaukee Road famously collapsed in the late 1970s, resulting in the largest right-of-way abandonment in the world). Since then, it has changed hands through other private owners, been stripped of its passenger services, and quasi-re-nationalised.

None of these actions have managed to stem the decline of the network.

The result of all of this? In 2001, most passenger services were shuttered across the country. For many lines, this meant their closure as well. Freight carriage had plateaued and the market was losing its share of tonnage to roading companies. By the time the Government repurchased the railways in 2008, things were heading downhill.

The average lifespan of a locomotive in this country was in the early 40s, and many wouldn't see withdrawal (some still haven’t) for another 10 years. Infrastructure and equipment had seen maintenance deferred to ensure infrastructure budgets didn’t cut into profit margins. And as the network was pared back, rural New Zealand had seen significant service cuts.

So, why are some people still pushing privatisation as a magic bullet if this was the case last time?

Money on the Mind

Since becoming an SOE, the network has consistently been expected to turn a profit, even at the expense of its much more valuable infrastructure impact. This led to largely similar conditions as the Milwaukee Road in the 1960s; cooking its books for a profit at the expense of investing in infrastructure.

The advocates for privatisation still spin the same tales, that the market will encourage better options, fairer prices, and faster travel. In other modes and other places, this could be true, but history tells us it is unlikely to ever work here. A good example to dispel this myth is the United Kingdom, where they pay some of the highest ticket fares in Europe, and face some of the worst service reliability rates.

That idea also belies another fact. Rail is a fundamental part of our infrastructure network.

Step back, and imagine selling our State Highway network to a trucking consortium. That is what happened when Wisconsin Central bought our rail network in 1993.

They are the only ones who need to invest in the network, but operational spending cuts into profit, so they defer maintenance and only invest in large returns (bulk customers). There’s no longer a requirement to have a connection or stop in your town as they aren’t common carriers anymore and there aren’t enough large customers to justify it.

This results in the wholesale withdrawal of rail from some areas of the country, even under government ownership.

Not a good model for the rest of us, right?

Is there a better way?

We have never sought to break up the rail monopoly, either in public or private form. And so, we continue to deny any competition in the market.

The problem with wholesale privatisation as we have in the past, is that it creates a de jure monopoly. And unlike road, some freights are unsuitable for transport by anything other than rail. Without a common carrier requirement, rail will only take large or profitable customers, much to the chagrin of local businesses. Imagine every log or coal train being replaced by the equivalent truckage. Mainfreight director Don Braid puts the additional truck trips required to cover non-rail-enabled Cook Strait ferries alone at 5,000 per year. Chaos springs to mind.

Poor management, asset stripping, and a desire to milk every cent from a cash cow were the conditions that precipitated the failure of The Milwaukee Road. These conditions might very well spell the end of our network should we not heed the warning to those who attempt to follow its path.

This is the problem with privatisation in New Zealand.

In the same way that our “gentailers” turn over record profits as our transmission network fails, and in the same way that our banks make the big bucks without investing in new technology or customer service improvements, we treat our infrastructure as a cash cow instead of part of a developed society.

The problem with that is that it will almost certainly lead to collapse. When infrastructure is undercut by profit margins, poor decision-making follows. And, the collapse of our rail network would be catastrophic for our economy and any hope we have for a low-emission future.

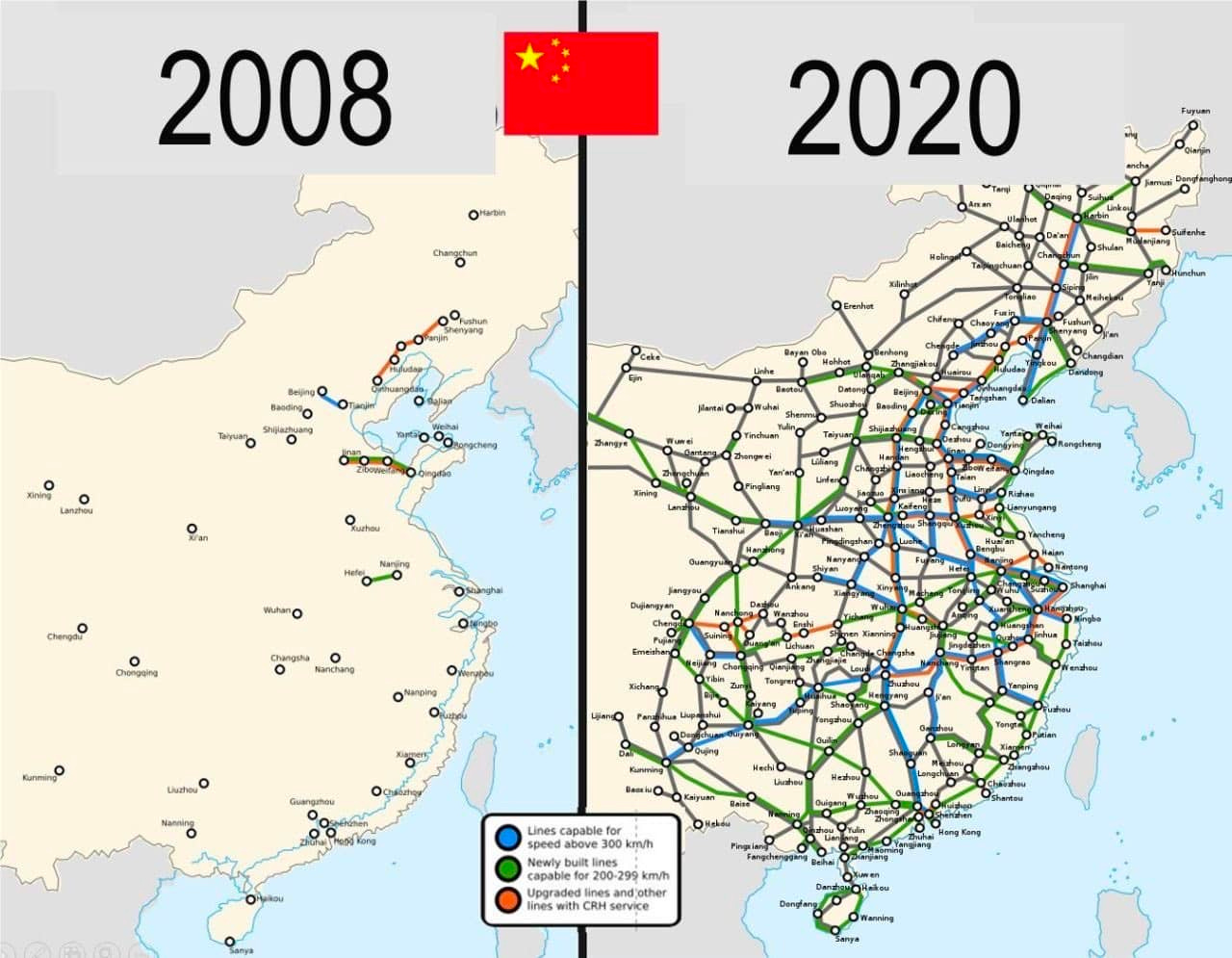

We stand to make ourselves a penny-rich, pound-poor country and fall ever farther behind the benchmark. While Europe is investing in new passenger services and sleeper trains, KiwiRail has settled on an impossibly expensive model of tourist trains. As U.S. railroads are seeing record freight haulage, freight carriage by rail in New Zealand has plateaued over the past decade. And as China has built 45,000km of high-speed rail since 2007, we’ve closed or mothballed large chunks of our network.

In the same way that Milwaukee Road’s management sought profit over sustainability, Kiwirail, Toll Rail, and TranzRail have all followed the same cookbook.

Looking at this, the options on the table are two-fold going forward.

Option one: Full Renationalisation.

Bring the whole network back under direct government control and remove the need for it to make a profit. Treat it as a full state asset and fund and use it to meet the needs of the people of this country.

Option Two: An Open Access Market with a Public Carrier

Allow competition on the network but maintain a base level of service through an SOE to keep the market in check (think DB or SNCF). This European Model also treats the physical infrastructure as a state asset rather than as a private asset.

Both options would still require immense investment from central government, an unavoidable fact.

Are Things Getting Better?

It’s not all doom and gloom. With proper funding, KiwiRail has secured two new classes of locomotives to replace the aged fleet and made significant repairs to large sections of the network in both islands.

The CNR DL class arrivals in the 2010s saw the displacement and retirement of the oldest stock. The arrival of the Stadler-built DM class in late 2024-2025 will see large swathes of outdated stock retired.

The rebuilding of Hillside workshops in Dunedin and the construction of the Waltham Mechanical Hub represent significant investments in the South Island and in the homegrown construction of rolling stock.

Major rebuilds of the Auckland Suburban network and the North Auckland Line as far as Whangarei offer potential, and there is a significant social movement to see more freight sent by rail. This is especially true in areas without current rail service, where bulk product such as lumber has to be taken by road, often with disastrous consequences. The long-awaited Marsden Point Spur could be a lifeline for Northland communities, and the reopening of the Gisborne-Napier line could offer better connections to the East Coast.

Renewed calls for passenger services have largely gone unheard by governments so far; but as Te Huia proves to be an undeniable success, and with many younger travellers thinking of carbon emissions, it seems only inevitable. Networks worldwide are seeing fresh interest in overnight sleepers and high-speed rail.

Should evidence return to the centre of policymaking any time soon, it will become hard to ignore the need to invest and change the model we use. A new phase of full privatisation is the last thing this country needs, and will ultimately put us on a path to becoming a dysfunctional nation. That much is clear to see.

Investment now will reap rewards for current and future generations. For all our sakes, let’s hope those with the chequebook start to understand that concept.

I totally agree, improved service and efficiency with privatization is almost always a lie.

i love the mountains