When is a Bus Lane not just a Bus Lane?

Cranford Street's bus lanes should be indicative of a larger plan at play. But what happens when push comes to shove and that plan doesn't work? What can we do to fix it?

If you’ve come looking for a submission guide on the Cranford St Bus Lane Trials, see Greater Ōtautahi’s one here. St Albans Resident’s Association Chair, Mark Wilson, also had an excellent piece related to this in the Christchurch Star this week.

Ah, the beauty of Cranford Street. A moving car park from 7-9 each morning and from 4-6 each evening, leaving a suburb split in two.

Discussions have raged on how to solve the ever-present traffic issue since before the Christchurch Northern Corridor even opened. The latest round of this frustrating debate is the decision on the temporary bus lanes. A topic that can somehow convince even the most ardently unengaged to think about public discourse and light a fire under even the most passive of residents.

But the options on the table seem lacklustre. Surely, such a pressing issue would demand the best solutions, using all available assets? In this case, however, the current arguments are too locally focused and the solutions don’t account for the root causes of the issues.

A Bridge Too Far? or a Poorly Designed Plan?

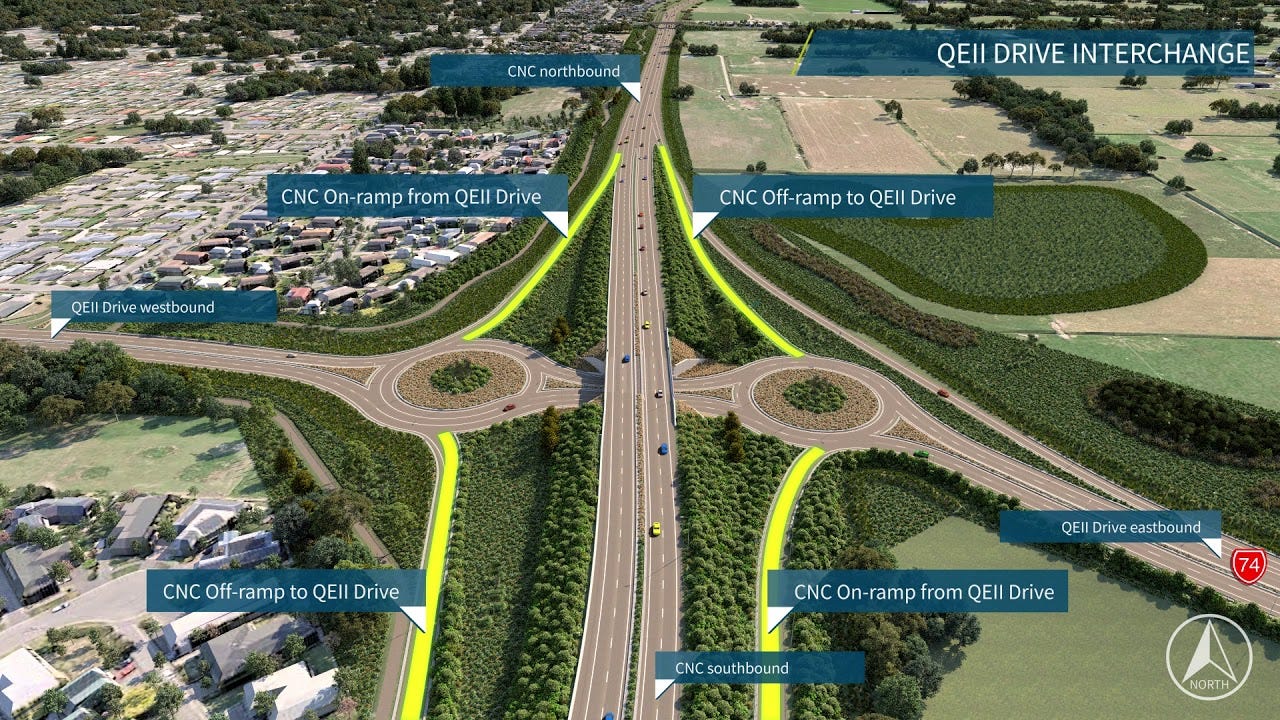

The issues at Cranford St began when the Christchurch Northern Corridor (CNC) opened. North of QEII Drive, it’s owned and operated by Waka Kotahi - the New Zealand Transport Agency. However, to get that sweet sweet funding, Christchurch City Council was required to join this corridor to Cranford St; in theory, creating a quick and easy way to get from the Waimakariri to the City.

Theory is a beautiful thing, right?

The reality has been nothing but headaches for residents and a thorough degradation of road safety in St Albans due to frustrated drivers. There is supposed to be a plan to deal with this; the much-touted Downstream Effects Management Plan (DEMP). Introduced in 2018, it has been the key part of CCC’s response to the increase in traffic. Local Board Member Simon Britten concisely outlines the timeline in this 2020 article. The DEMP is a reactionary framework, and at the pace bureaucracy moves it leaves residents and community in the lurch. Despite CCC’s requirement to review traffic levels, any problem have existed for several years by the time anything is done.

The bus lanes are simply tinkering around the debate that needs to be had at large, just like the discussions around Flockton St and Francis Ave were. The real question is why such high volumes of traffic were allowed to flow through an inner-city suburb in the first place, and why do the only solutions fail to recognise the causes of this?

A Constant Headache for Residents

The theory behind the DEMP subscribed to the idea that if we built easy-to-follow and clear pathways for vehicles entering and leaving the city, they would use them. Straightforward enough? Planners seem to forget about a little concept known as induced demand.

Streets that were once safe for residents can change overnight to respond to increased demand. If you’re interested in this concept and debate around road engineering, I recommend Confessions of a Recovering Engineer by Strong Towns’ Charles Marohn.

Concerns have been at large for years since the project was completed about walkability in school zones and the impact on foot traffic for local businesses. Westminster St is protected by lights and a crossing guard, yet near misses show up on community group pages at an unsettling rate. In 2020, Police had to patrol the Cranford St and Westminster St intersection due to dangerous driving. Residents on side streets report anti-social driving, and walking around Cranford St is not for the faint of heart.

Residents now face extended journey times in their suburbs and have become disconnected from the amenities that form the core of their community. Accessible walking routes now require careful timing to nip between traffic, and the kerb-to-kerb distance is more now than ever. Data collected by students at the University of Canterbury in 2020 showed close to 80% of residents in St Albans believed that the Northern Arterial would make it harder to get around their suburb.

Schools are concerned for the safety of students and parents are even less likely to approve of their children cycling or walking with higher levels of traffic; ironically creating more traffic as they have to drive their children to keep them safe. 2023 and 2024 saw St Albans School raise significant concerns for the safety of children travelling to and from the school which the DEMP is failing to provide.

The Wider Problem with the DEMP

The majority of traffic that uses the CNC is from the Waimakariri and Hurunui Districts, the result of significant population growth in the aftermath of the 2011 Earthquake and through lower land prices in the regions attracting new developments. The DEMP only looks at addressing these issues once they hit St Albans. That’s the wrong attitude to have.

Proactive incentives to get drivers off the road have shown success, but have not been scaled up to the size required to have a major impact. The 91 Rangiora - City Direct and 92 Kaiapoi - City Direct buses are well-patronaged and efficient. However, these services can be unreliable and infrequent, and the scheduling of the 91 and 92 are hardly flexible for many.

It’s fair to say some of the resistance to bus lanes boils down to perceived low usage. Greater Auckland ran a piece back in 2017 outlining why bus lanes can be seen this way despite ranking amongst some of the most efficient infrastructure. A recent Local Government Official Information and Meetings Act (LGOIMA) request has found that CCC has no data on enforcement for the Cranford St Bus Lanes, indicative of a lack of enforcement.

Other options like heavy passenger rail for this city seem further away now than at any point in the last decade. There’s little commitment from the central government to fund more options across the region. Then there are the T2 lanes on the CNC that were designed to help encourage carpooling and ridesharing. NZTA is de facto not enforcing them, ensuring no tangible impact. On top of this, the government has promised a major new motorway to bypass Woodend. This will only guarantee more traffic on our streets.

The lack of timely, large-scale infrastructure to reduce car patronage is possibly the biggest thing the CNC and the DEMP must deal with. They aren’t, so why do we allow this to be the status quo? International and local evidence around transport engineering has vast swathes of data and case studies, full of solutions we choose to ignore.

So how should we respond? Not by building and destroying more roads, that’s for sure.

An Upstream Cause Management Plan?

None of the problems with Cranford St can be solved by simply managing the traffic once it arrives. There are options to help though.

The best option requires greater involvement from ECan and the provision of a much more mature public transport service pattern from Waimakariri and Hurunui. Groups have been advocating since 2011 for better public transport to the north, and the expansion of the “Direct” bus services in frequency and reach is an easy place to start.

Other options must include further active transport infrastructure such as more crossing points and better management and enforcement of existing routes. As early as 2015 St Albans School students were advocating for Barnes Dance crossings at Westminster St, an action that would shift ownership of that space away from vehicles and back to people.

A mature transit system requires a degree of priority for public transport on major corridors. This is where the discussion around Cranford St’s issues should focus. Once we tackle that issue and develop a much more advanced transit network (both now and looking towards the future), the other safety and connectivity issues become much easier to solve. Better and safer local connections will improve people’s access to amenities and reduce local traffic, making streets safer, and our neighbourhood more livable.

The issue is solvable, but it will take many actions currently off the table under the DEMP. Drivers drive because they have, or at least believe in, no other choice to ensure they meet the ever-tightening demands of employment and life. A mature transit system would go a long way to ensuring that perception or reality is changed. More crossings and safer designs suddenly become possible when we put people before cars. There’s no reason to suggest this wouldn’t work.

As a community, that would be a breath of fresh air for many, but it takes that change in priority for our action.