Rates C(r)aps

Alternatives to this government's rates cap proposals that could have more impact.

This post was originally published on November 19th. It has been updated as of December 3rd to reflect new policy announcements from the Government, and new commentary from local officials and media. I’ve also included some more commentary around asset sales.

Rates caps aren’t the solution to local government’s financial woes.

Despite commentary yesterday in The Press, and Simon Watts’ continuous preaching about the inability of local government to ‘balance the books’, the truth remains: local government is woefully underfunded to deliver the basics. In a somewhat ridiculous situation, a lot of the rates blowouts for councils are being driven directly off the back of central government’s decisions - not ‘nice to haves’.

If commentators and this government were serious about the long-term stability of local government, they would be discussing new funding avenues, rather than shackles.

Let’s explore some of those.

Why not cap rates?

On December 2nd, Local Government Minister Simon Watts announced a government policy of capping rates within a 2-4% band. This policy will not take effect in full until 2029, but Councils will be required to consider it from 2027, and the Minister has threatened that interventions could take place under the Local Government Act any time from now.

Capping rates sounds great until you put it into practice. Limiting the ability of councils to respond effectively to population growth, natural disasters and other significant funding shortfalls is a dangerous precedent to set.

Mayors in the United Kingdom and Australia have hit back at proposals implemented there, with mayor of the Northern Beaches Council, Sue Heins, outlining to LGNZ the long-term issues 40 years of rates capping has brought across the ditch:

“Where the choice was between fixing a collapsing seawall or a safety issue in one of their community centres because their lighting has failed.

“Which one is the most unsafe? Those are the decisions you start making when you are reducing your services.”

Treasury advice has also noted that capping rates could have a significant impact on the credit ratings and stability of local government authorities, and that rates are not sustainable.

Under scrutiny, rates caps present significant long-term financial risk to councils, with limited benefits. It is likely significant cuts and deferrals to critical infrastructure will be needed to meet these arbitrary goals.

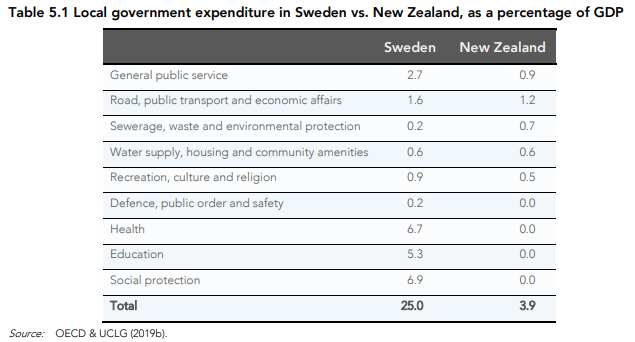

Former Local Government New Zealand President Sam Broughton said that “despite council’s ever-increasing responsibilities, local government’s share of overall tax revenue has remained at 2% of GDP for the last 50 years”. This is despite a New Zealand Productivity Commission report in 2019 noting that Local Government investment constituted ~4% of GDP1.

If that’s true and we are being honest with ourselves, it means local government as a sector is far more efficient and careful with its spend than central government.

So, what can we do instead?

Why don’t central government properties pay rates?

Remarkably, despite the government’s continued rhetoric around ratepayers being squeezed, they themselves aren’t good ratepayers.

Government owned properties are exempt from local rates, meaning that despite hospitals, schools, prisons, and other central government facilities using our local roads, water infrastructure, and Council facilities, they don’t pay for it.

Now, the Minister will argue that the Crown already pays its fair share through investment in local projects. And that would be fine, if it didn’t continually saddle local government with the responsibility to insure, maintain, and operate these facilities on their own.

This imbalance deprives local authorities of millions of dollars of rateable property, usually in the urban core of our cities. The Ministry of Education portfolio is composed of over 2,100 primary and secondary state schools and over 8,000 hectares of land with a carrying value of $33.5 billion alone.

According to The Press’ Charlie Mitchell, the government is Christchurch’s biggest rates-dodger.

The Press has analysed more than 180,000 property records and sought to estimate the Crown’s outstanding rates bill in Christchurch.

We found it’s approximately $25 million per year, which is not pocket change. If the city council used that $25m solely to offset rate increases it would equate to about three percentage points. This year’s projected rates increase of 6.6% would fall to 3.6%.

Paying rates on central government property would provide an immediate new source of revenue for councils.

Why isn’t ACT’s policy of GST on new builds being returned to the regions being prioritised?

This coalition government has decided to pursue rates capping as a political strategy.

One would almost call it ‘pork-barreling’, given its announcement in proximity to the local elections, supporting aligned candidates and forcing others into an unfavorable public position.

In a somewhat silly turn then, ACT’s election policy of returning GST on new build homes to local authorities seems to have been abandoned or deprioritised altogether. Very little has been said of this policy since April this year.

A policy that would reward regions for consenting and building more properties, this could fundamentally support the regions with the highest growth rates, and by extension the most significant infrastructure burdens to overcome.

One has to wonder why this policy has not come to fruition 2 years on from the election.

Why do we still pay GST on our rates?

In perhaps an oversimplified sense, a tax on a tax.

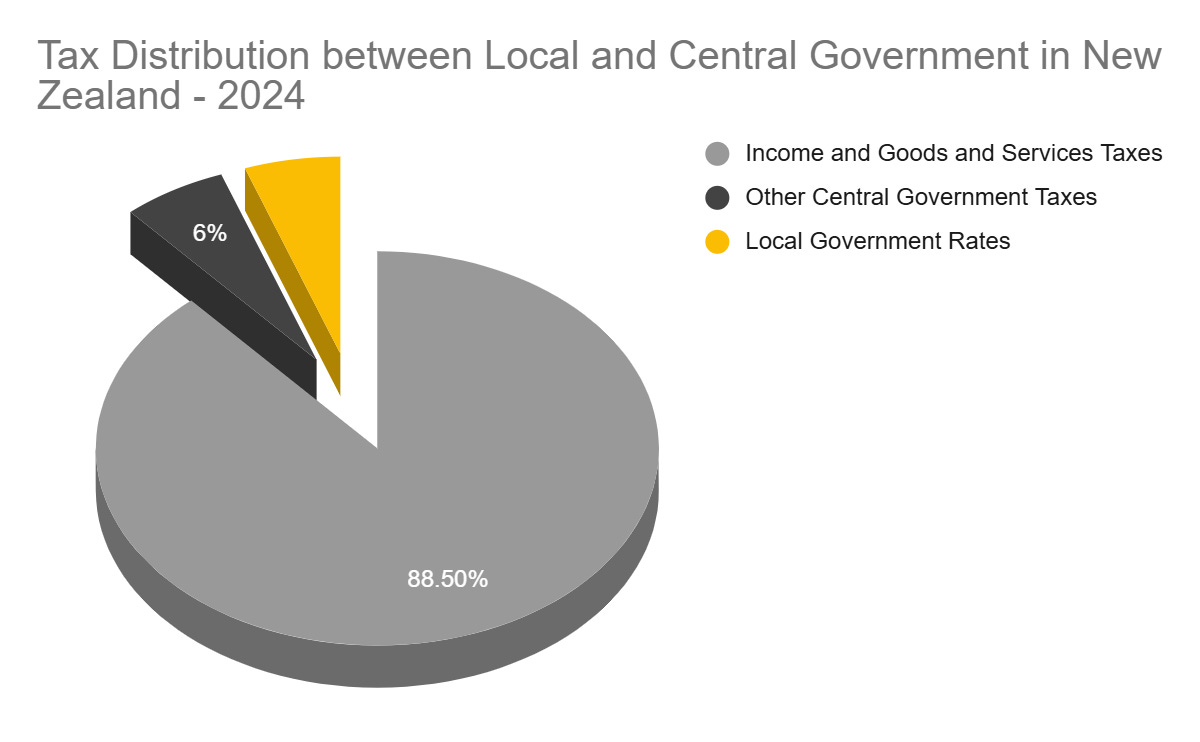

So that begs the question, is it fair for 15% of your rates bill to go straight to Wellington? Many would argue not given the imbalance of tax take in this country and the increasing responsibility of local authorities.

It deprives councils of potential income, by sending it to central government; which provides no guarantee of local reinvestment. And because it is councils who have to set the rates take, they cop the flak for this.

LGNZ estimated in 2024 that this could provide local authorities with a combined NZ$1.1B more in revenue. Infometrics Chief Executive and Principal Economist Brad Olsen noted that “In total, 29 of the 78 councils across New Zealand would receive more than $10m if GST on rates was returned to councils”. For larger authorities, it would be expected to be a significant boost.

Again, Mitchell’s research brings dividends.

For Christchurch, this equates to around $120m a year. If the Crown also paid rates on its properties, those two changes wouldn’t just soften rate increases, they would reverse them.

The expected 6.6% rates rise could instead turn into an 8% cut.

This one is a real no-brainer.

What about our assets?

Recent commentary has brought back the ugly rhetoric of asset sales, something particularly prominent here in Ōtautahi Christchurch.

Within 48 hours of the Minister’s announcement to cap rates, National Party stalwart and Councillor Sam MacDonald had already proposed the sale of Enable, Christchurch’s Council owned fibre-broadband provider. It’s entirely plausible to believe that this will not be the extent of sales should this position continue; and while most of the sitting Council signed Keep Our Assets’ no-sale pledge, rates caps were speculative at that time.

And, while we could have faith that Councillors will abide by their promises, there’s no sure way to tell what could happen if rates do not fall within the 4% threshold.

Christchurch is already dealing with the aftermath of Government appointed commissioners to Environment Canterbury, and if the Minister is to be believed, any Council not making that threshold could face a similar fate.

Cantabrians overwhelmingly rejected the possibility of asset sales in polling during the election, but commissioners aren’t answerable to the people. The Government could strip our assets from under us to pay for their promises, crippling the ability of future generations to have the same opportunities.

Food for thought.

Changing these situations would provide immediate financial relief for councils and ratepayers alike. It offers the opportunity to rebalance the scales that have traditionally been held firmly in central government’s favour.

To do this however, would require a government that was willing to engage with these ideas in good faith, and local leaders willing to hold them to account. For a Council who resoundingly sent the previous Government a middle finger, there is a resounding silence this time.

And, given the recent rhetoric and historical precedence, I doubt that change is happening anytime soon.

This figure is likely to have risen due to inflation in core Local Government responsibilities outstripping the pace of inflation.